A long strangle is a limited risk/unlimited profit strategy that looks a lot like its trading cousin, the straddle, save for one detail: While straddles are initiated with both options at the money, strangles are set with both options out of the money.

And what does that mean in practice?

Well, because a long strangle consists of one call purchased above the current price of the underlying security and one put purchased below (both options out of the money), the price of the strangle is always cheaper than a straddle.

Tradeoffs and Pitfalls

For the average investor trying to decide between trading a straddle or strangle, the choice, indeed, comes down to two factors: the initial cost of the trade; and the probability of profit.

That is, the long straddle and strangle are both bullish on volatility, and therefore have to see an appreciable move in the underlying in order to claim a profit. That said, the straddle’s cost of entry is much higher, as it offers a greater chance of profit should the underlying begin its move earlier, while the options still possess a greater proportion of time value.

On the other hand, the strangle offers far more bang for the buck should the underlying move very far into the money late in the trade. Under those circumstances, a relatively cheap initial layout would result in a greater reward percentage-wise than the straddle.

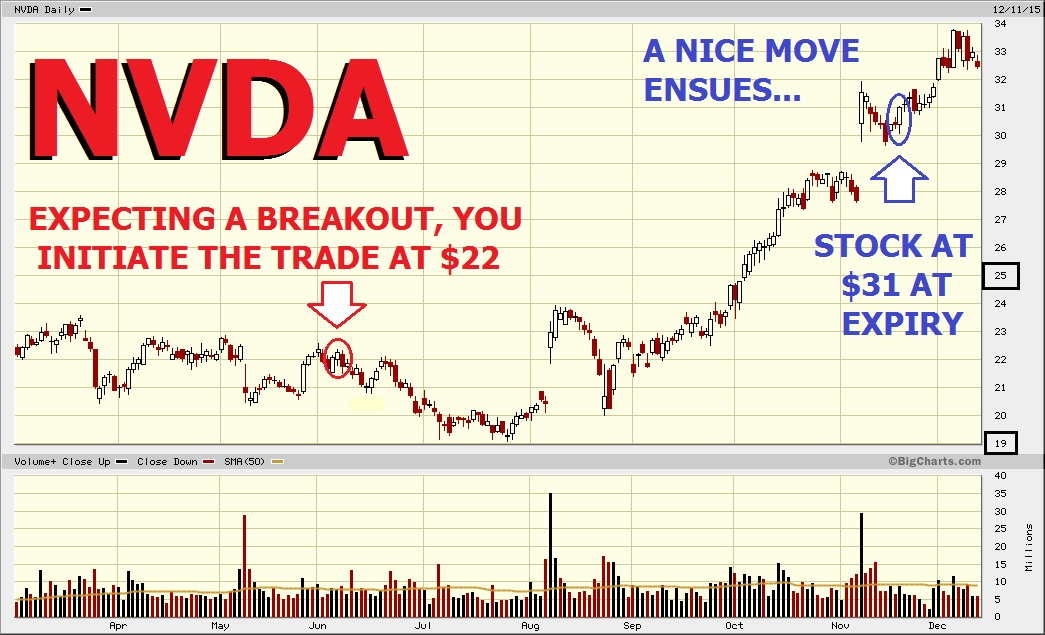

Take a look now at a chart of computing wise-guy Nvidia Corp. (NASDAQ: NVDA) to better appreciate the long strangle strategy.

Your research suggests that after months of sideways drift, Nvidia shares are due for a breakout. You’re not certain which way the move will come, so you weigh your options.

With the stock sitting at $22, a five-month straddle will cost you exactly $5 (22 call and 22 put at $2.50 each), while a strangle, using the 19 and 25 strikes, comes out to just a dollar (black squares).

Because you don’t have a great deal of money to commit to the trade – and because you’re relatively sure forthcoming news will trigger a big move in the stock – in the first week of June you dive in and buy the strangle (red circle).

Results!

It takes another two months before Nvidia starts to trend, but when it does, the move is sharp.

The stock flies higher on the signing of a massive licensing deal and closes at $31 by November expiry. Your put expires worthless, but the call is in the money $6 ($31 – $25), leading to a $500 net gain ([$6 – $1] x 100).

After the win, you consider what the outcome would have been had you purchased the straddle. Again, the put would have expired worthless, but the call would have ended up $9 in the money, leading to a net gain of $400 ([$9 – $5] x 100) – less than the strangle, and for a considerably greater initial cost.

Break-Even Points

The straddle would have broken even at $27 and $17 (strike price +/– initial premium), while the strangle’s break-even points are $26 and $18 (call strike price + initial premium, put strike price – initial premium).

As mentioned above, had the stock moved early to, say, $25 or $26 and stayed there, an early closure of the straddle would have produced a superior profit, due to the time value still inherent in the options.

Source: http://www.wyattresearch.com/article/long-strangle/